Numerical Atlas Annotation Documentation

Welcome to the Numerical Atlas annotation project documentation. The following sections will introduce you to the annotation schema will shall be using for this project, and the annotation tool which shall be employing (brat rapid annotation tool).

Table of Contents

Project Goal

The goal of this project is to produce a tool to automatically extract measurements from the astrophysical literature. ‘Measurement’ in this context refers to a numerical value associated with a named entity - for example the “Hubble constant”, or “the mass of Jupiter”. We hope to be able to extract and record the names, symbols, measured values, uncertainties, units, and confidence limits of measurements present in the text of astrophysics papers.

We have written a first paper discussing our baseline models and initial steps with neural network models, which may be found here (submitted to the Monthy Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society).

To move further with the project we now require a corpus of annotated examples to use as training data for more complex neural models (using sequence modelling and recurrent networks). That is where you come in. This documentation will help explain the basics of annotating abstracts of astrophysical papers using brat and the annotation schema we have created.

Glossary

A brief glossary to help you with the natural language processing (NLP) terminology:

- Entity:

- Relation:

- Attribute:

brat

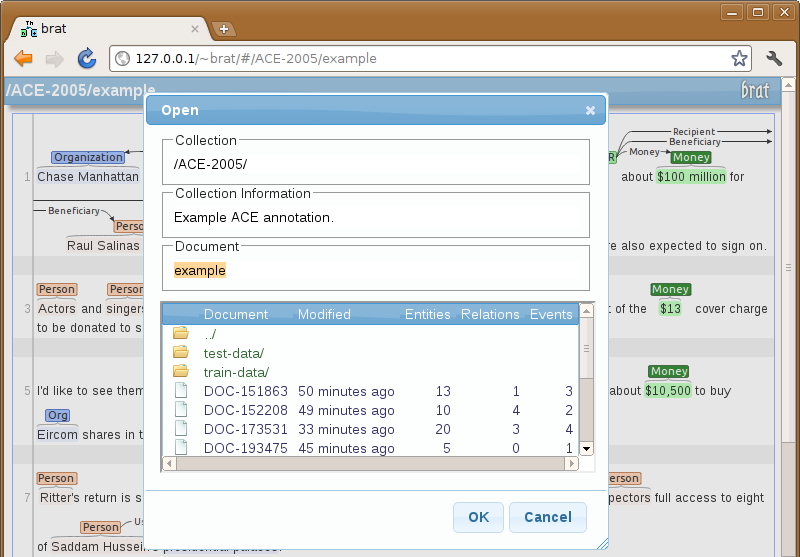

The brat rapid annotation tool (brat) allows for annotators to create and edit annotations from a browser. Google Chrome and Safari (desktop) are the only fully suppported browsers (Firefox has visualization support, but only partial editing support, and is not recommended). Mobile browsers are not supported at all.

A link and login to our brat server will be emailed to you when you sign up to help with this project. Please get in touch if these do not work. Once you have logged in, you should see the brat interface.

From here, navigate to your annotation directory, select a paper, and you may begin annotating.

Entity annotations are made by selecting spans of text with the cursor. Once selected, a window will appear allowing you to select the appropriate entity label, and any necessary attributes for the annotation. Relation annotations are made by clicking-and-dragging from one annotation to another. If a potential relation exists between the start and end annotations (and do note that some annotations are directional) a window will appear asking you to confirm the relation type. Note that once the appropriate entity/relation label has been selected in these windows, the selection may be confirmed by pressing the Enter key.

An introduction to the brat interface may be found here.

Annotations

Entities

The primary goal of this project is to link numerical measurements to physical entities in free text, and as such this is the backbone of our annotation process. Numerical measurements are relatively easy to identify in free text, and here are classified into two forms: measured values, and constraints. Physical entities are a little more complex in the ways they may be represented in text. Here we annotate them using three primary Entity labels: Parameter Name, Parameter Symbol, and Object Name. These different labels are discussed below:

MeasuredValue

An example of a measured value would be:

H _ { 0 } = 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 } ( 1 \sigma )

T1 ParameterSymbol 0 9 H _ { 0 }

T2 MeasuredValue 12 54 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 }

T3 ConfidenceLimit 58 65 1 \sigma

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

Alternatively, as a range:

H _ { 0 } = 68 - 72 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 } ( 1 \sigma )

T1 ParameterSymbol 0 9 H _ { 0 }

T2 MeasuredValue 12 50 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 }

T3 ConfidenceLimit 53 61 1 \sigma

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

When annotating a measured value, please include the central value or range, along with any uncertainties and units that may be given. This includes any bracketed notes which may accompany the uncertainties, as shown in this example:

w = -0.81 ^ { +0.16 } _ { -0.18 } ( \mathrm { stat } ) { \pm 0.15 } ( \mathrm { sys } )

T1 ParameterSymbol 0 1 w

T2 MeasuredValue 4 87 -0.81 ^ { +0.16 } _ { -0.18 } ( \mathrm { stat } ) { \pm 0.15 } ( \mathrm { sys } )

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

Further, please note that measurements may sometimes be given with percentage uncertainties, expressed after the given units (if present). This is a separate case from both SeparatedUncertainty and ConfidenceLimit - please examine such cases carefully, however, to ensure you have the correct annotation for the situation. An example of a percentage uncertainty to be included in a MeasuredValue would be:

We also measure the mass of the central black hole to be 1.09 \times 10 ^ { 7 } M _ { \odot } \pm 14 \% .

T1 ParameterName 20 24 mass

T2 Object 32 50 central black hole

T3 MeasuredValue 57 105 1.09 \times 10 ^ { 7 } M _ { \odot } \pm 14 \%

R1 Property Arg1:T2 Arg2:T1

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

Please note that not all MeasuredValues will follow an equals sign. Some may use other similar symbols, such as \sim, or may use no equivalence sign at all.

Measured values in a scientific context should have at least one uncertainty associated with them (unless given as a range, in which case the uncertainty is implied rather than stated), but it is possible that this uncertainty may be given somewhere else in the text. If this is the case, please use the SeparatedUncertainty annotation below. If you encounter a value with no uncertainty, which is nonetheless clearly linked to some physical entity, it may require an attribute to be attached to the annotation (which may be done from the window which appears after a span is selected with the cursor, or when double-clicking on an existing annotation) such as the From Literature attribute. If none of the attributes seem appropriate, please consider carefully whether this value really constitutes a measurement, or if it is merely some contingent value to another statement in the text. For example, in the following:

We achieve a distance measure at redshift z = 0.275 , of r _ { s } ( z _ { d } ) / D _ { V } ( 0.275 ) = 0.1390 \pm 0.0037 ( 2.7 % accuracy )

T1 ParameterName 13 29 distance measure

T2 ParameterSymbol 57 102 r _ { s } ( z _ { d } ) / D _ { V } ( 0.275 )

T3 MeasuredValue 105 122 0.1390 \pm 0.0037

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

The “redshift z = 0.275” is definitely not a MeasuredValue, despite having a name, symbol, and value.

However, in the following case, the author of the paper is making a statement about a measureable quantity (“\Omega _ \Lambda”):

... our results are consistent with a standard flat \Omega _ { \Lambda } = 0.7 " concordance " model ...

T1 ParameterSymbol 52 72 \Omega _ { \Lambda }

T2 MeasuredValue 75 78 0.7

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

A1 FromLiterature T2

(See on arXiv)

In this case, while the author is not quoting a novel measurement, they are still expressing information regarding a measureable quantity. As such we are definitely interested in this information, and would like it to be annotated as a MeasuredValue - however, in this case, with a FromLiterature attribute.

Many unusual units or parameterisations may be used to display measurements in text, and we ask if you could include them in the MeasuredValue (or similar) annotation (bearing in mind that we are not using overlapping annotations for this project). For example, in the following, \Omega _ { m } is both used to parameterise the measurement of \sigma _ { 8 }, but is not annotated as a ParameterSymbol inside the MeasuredValue:

we obtain \sigma _ { 8 } = ( 0.508 \pm 0.019 ) \Omega _ { m } ^ { - ( 0.253 \pm 0.024 ) } , with \Omega _ { m } < 0.34 at 68 per cent confidence

T1 ParameterSymbol 10 24 \sigma _ { 8 }

T2 MeasuredValue 27 89 ( 0.508 \pm 0.019 ) \Omega _ { m } ^ { - ( 0.253 \pm 0.024 ) }

T3 Constraint 97 118 \Omega _ { m } < 0.34

T4 ConfidenceLimit 122 133 68 per cent

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T3 Arg2:T4

(See on arXiv)

A MeasuredValue annotation may also require an “Attribute” to be set to indicate additional information about the stated measurement. These are discussed below.

Please read the text around measurements carefully, as additional measurements (for example, the same quantity under some subtly different assumptions) can easily be missed. For example, there are two measurements of “\beta” here, which should both be annotated:

... the redshift-distortion parameter \beta = 0.49 \pm 0.16 for r = 1 ( \beta = 0.47 \pm 0.16 without finger-of-god compression ) ...

T1 ParameterName 8 37 redshift-distortion parameter

T2 ParameterSymbol 38 43 \beta

T3 MeasuredValue 46 59 0.49 \pm 0.16

T4 ParameterSymbol 72 77 \beta

T5 MeasuredValue 80 93 0.47 \pm 0.16

T6 Detail 64 69 r = 1

T7 Detail 94 130 without finger-of-god compression

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T4

R3 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

R4 Measurement Arg1:T4 Arg2:T5

R5 Condition Arg1:T3 Arg2:T6

R6 Condition Arg1:T5 Arg2:T7

(See on arXiv)

SeparatedUncertainty

If you encounter a measurement with an uncertainty given separately in the text, annotate the uncertainty with a SeparatedUncertainty annotation, and link it to the MeasuredValue with an Uncertainty relation (see below). An example of this would be:

...is found to be around 0.39 GeV cm ^ { -3 } with a 1- \sigma error bar of about 7 %...

T1 MeasuredValue 25 45 0.39 GeV cm ^ { -3 }

T2 ConfidenceLimit 53 62 1- \sigma

T3 SeparatedUncertainty 82 85 7 %

R1 Confidence Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Uncertainty Arg1:T1 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

Constraint

The Constraint annotation is used for values which specify an upper or lower bound on a quantity. For instance, in the following example we have two Constraints on the ParameterSymbol “\Omega _ { k }”:

-0.0179 < \Omega _ { k } < 0.0081 \mbox { ( 95 \% CL ) }

T1 Constraint 0 7 -0.0179

T2 Constraint 27 33 0.0081

T3 ParameterSymbol 10 24 \Omega _ { k }

A1 LowerBound T1

A2 UpperBound T2

T4 ConfidenceLimit 44 49 95 \%

R1 Measurement Arg1:T3 Arg2:T1

R2 Measurement Arg1:T3 Arg2:T2

R3 Confidence Arg1:T1 Arg2:T4

R4 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T4

(See on arXiv)

We use the UpperBound and LowerBound attributes to specify the nature of the constraint. These are discussed below.

When annotating a constraint, please include both the value and any associated units.

It is perfectly possible that a constraint may be given in the text without the use of equality symbols, as in the following:

Allowing the inclination to be a free parameter we find a lower limit for the spin of 0.90 , this value increases to that of a maximal rotating black hole when the inclination is set to that of the orbital plane of J1655-40 .

T1 ParameterName 13 24 inclination

T2 ParameterName 78 82 spin

T3 Constraint 86 90 0.90

T4 ParameterName 164 175 inclination

T5 Object 215 223 J1655-40

R1 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

A1 LowerBound T3

(See on arXiv)

Please do check carefully for cases such as this, as we would definitely like to capture these more complex relationships between parameters and constraints in free text.

Please note that range values (e.g. “46 - 54 km s ^ { -1 }”) should be annotated as a single MeasuredValue, rather than a Constraint (or pair of Constraints).

Also, constraints may be quoted from other sources (either as quoted measurements, or standard assumed constraints). Please do annotate these as Constraint entities with FromLiterature attributes.

Physical Entities

A physical entity here is considered to be a property (either of the Universe or a specific object) which may be measured in some way to produce a numerical result. For instance, we may measure the Hubble Constant (property of the Universe), or the radius of the Milky Way Galaxy.

ParameterName

Property names are identified using the Parameter Name annotation. This annotation is specifically for written (i.e. linguistic) names of physical entities. For example in the following sentence:

...this time-delay estimate yields a Hubble parameter of H _ { 0 } = 52 ^ { +14 } _ { -8 } ~ { } { km } ~ { } { s ^ { -1 } } ~ { } { Mpc ^ { -1 } } ( 95 \% confidence level ) where...

T1 ParameterName 37 53 Hubble parameter

T2 ParameterSymbol 57 66 H _ { 0 }

T3 MeasuredValue 69 147 52 ^ { +14 } _ { -8 } ~ { } { km } ~ { } { s ^ { -1 } } ~ { } { Mpc ^ { -1 } }

T4 ConfidenceLimit 150 155 95 \%

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

R3 Confidence Arg1:T3 Arg2:T4

(See on arXiv)

note that the written name has a separate annotation to the mathematical symbol. The two should be linked by the annotator, however, as discussed below.

Umbrella terms are not, themselves, ParameterNames (e.g. “cosmological parameters”). To determine if something qualifies as a ParameterName, consider whether it is something you can measure - if yes, then it is quite probably worthy of being annotated as a ParameterName.

Parameter names can become complicated due to being dependant on other parts of the text (for instance, when the word “radius” is used as a parameter name, what is it the radius of?). This is discussed below in the section on the Object entity.

Please annotate all instances of Parameter Names that you encounter - even if they are not directly tied to a mathematical symbol or measurement. For instance, in the following sentence:

...suggesting that the combination of these two independent phenomena provides an interesting method to constrain the Hubble constant .

T1 ParameterName 118 135 Hubble constant

(See on arXiv)

the annotation is helpful, as it aids the entity recoginition phase of our model training. If something is obviously (to you) a parameter of some kind, even if not directly related to a measurement, please do annotate it, along with any accompanying ParameterSymbols and appropriate relations.

Exactly where a parameter name begins and ends is a judgement call for the annotator - do be aware that in astrophysical contexts names can become rather verbose, as in the following:

The mass ratio of non–baryonic dark matter to baryonic matter is 3.1 ^ { +2.5 } _ { -2.4 }

T1 ParameterName 4 61 mass ratio of non–baryonic dark matter to baryonic matter

T2 MeasuredValue 65 90 3.1 ^ { +2.5 } _ { -2.4 }

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

In such cases, please use your judgement to decide if the name qualifies as a single entity, or should be divided into an Object-Property relation (see below and in the relations section). Generally, if a ParameterName seems to contain the name of an object (e.g. a specific star) or class of objects (e.g. “galaxies”, “white dwarfs”, “neutrinos”) please separate the ParameterName into separate Object and ParameterName annotations. For example, the contrived ParameterName(“critical mass of white dwarfs”) becomes Object(“white dwarfs”)-Property-ParameterName(“critical mass”).

ParameterSymbol

Mathematical symbols are annotated separately to the written names of physical entities. When a mathematical symbol appears next to a written name, please ensure that you give separate labels for each, as in the following example:

...significantly reduces the uncertainty in the optical depth parameter , \tau .

T1 ParameterName 48 71 optical depth parameter

T2 ParameterSymbol 74 78 \tau

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

...where r _ { s } ( z _ { d } ) is the comoving sound horizon at the baryon drag epoch...

T1 ParameterSymbol 9 32 r _ { s } ( z _ { d } )

T2 ParameterName 40 87 comoving sound horizon at the baryon drag epoch

(See on arXiv)

Note that due to our text being derived from LaTeX source files, there may be some fairly convoluted TeX syntax within the spans for mathematical symbols. Please take the time to properly determine the start and end of these symbols, as this will be very helpful for training our future models. An example of this kind of TeX would be:

Hubble constant H _ { \lower 2.0 pt \hbox { \$ \scriptstyle 0 \$ } } = 61.7 ^ { +1.2 } _ { -1.1 } \hbox { km } \hbox\% { sec } ^ { -1 } \hbox { Mpc } ^ { -1 }

T1 ParameterName 0 15 Hubble constant

T2 ParameterSymbol 16 68 H _ { \lower 2.0 pt \hbox { \$ \scriptstyle 0 \$ } }

T3 MeasuredValue 71 158 61.7 ^ { +1.2 } _ { -1.1 } \hbox { km } \hbox\% { sec } ^ { -1 } \hbox { Mpc } ^ { -1 }

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

You may encounter situations in which a ParameterSymbol is given in two forms. For example, in the following, we have a parameter \beta, which is measured for two different scenarios:

We find \beta _ { I } = 0.42 ^ { +0.10 } _ { -0.06 } and \beta _ { O } = 0.26 \pm 0.08

T1 ParameterSymbol 8 21 \beta _ { I }

T2 MeasuredValue 24 52 0.42 ^ { +0.10 } _ { -0.06 }

T3 ParameterSymbol 57 70 \beta _ { O }

T4 MeasuredValue 73 86 0.26 \pm 0.08

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Measurement Arg1:T3 Arg2:T4

(See on arXiv)

In such cases, please annotate each subscripted (or otherwise demarcated) symbol as its own ParameterSymbol, as above.

It is also worth noting that a ParameterSymbol may itself be a mathematical expression. For example:

... that match CMBR in our spectral bands of \Delta T / T = 1.9 ^ { +1.3 } _ { -0.7 } \times 10 ^ { -5 } ...

T1 ParameterSymbol 45 57 \Delta T / T

T2 MeasuredValue 60 104 1.9 ^ { +1.3 } _ { -0.7 } \times 10 ^ { -5 }

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

As for ParameterNames, please annotate all instances of ParameterSymbols you encounter, even if they appear independently of any measurements or ParameterNames. If something is obviously (to you) a parameter of some kind, even if not directly related to a measurement, please do annotate it, along with any accompanying ParameterNames and appropriate relations.

Observations of megamaser disks in other galaxies will further reduce the uncertainty in H _ { 0 } as measured by the MCP .

T1 ParameterSymbol 89 98 H _ { 0 }

(See on arXiv)

A caveat to this is in the case of equations: a separate annotation, Definition, exists for this situation. See below.

Object

Global properties (e.g. Hubble constant) may usually be identified in free text by their name (or symbol, if a recognisable one exists) alone, but this is often not the case for properties of objects. For example, consider the following sentence:

The inclination of this system is estimated at 55 ^ { +2 } _ { -7 } degrees .

T1 ParameterName 4 15 inclination

T2 MeasuredValue 47 75 55 ^ { +2 } _ { -7 } degrees

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

Here we have no indication of what object “inclination” relates to. In cases such as this, however, the object is generally referenced somewhere else in the text, and we use the Object Name annotation to identify this object. We may then link the Object Name to the Parameter Name or Parameter Symbol annotation (preferring the written name if available) using the Property relation as described in the relations section.

In the case where the object and property appear in the same sentence, please annotate the Object name and ParameterName separately, as in the following examples:

Using this technique we find the mass of the Milky Way to be 0.85 ^ { +0.23 } _ { -0.26 } \times 10 ^ { 12 } M _ {\odot} .

T1 ParameterName 33 37 mass

T2 Object 45 54 Milky Way

T3 MeasuredValue 61 120 0.85 ^ { +0.23 } _ { -0.26 } \times 10 ^ { 12 } M _ {\odot}

R1 Property Arg1:T2 Arg2:T1

R2 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T3

(Constructed example.)

Please annotate all instances of Object Names that you encounter, even if they are not directly linked to properties or measurements, as this aids our entity recognition models. Generic objects (e.g. “supernova”, “galaxies”) shouldn’t be annotated as Objects unless they function as such in the sentence, however. But specific names (e.g. “NGC 571”, “Ceta Ori”, “Local Group”) should always be annotated.

This nuclear GC has luminosity , color , and structural parameters similar to that of \omega Cen and M 54...

T1 Object 86 96 \omega Cen

T2 Object 101 105 M 54

(See on arXiv)

Determining when to use an Object annotation, rather than incorporating it into a ParameterName or simply leaving it out of the annotation, can be difficult. In general, if you encounter a situation where you have a parameter name which requires the context of another entity to be understood, then annotate that entity as an Object. For example, if we have (a contrived sentence), “Considering neutrinos, we find the average mass to be NUMBER”, then “neutrinos” is operating as an Object in this sentence - mostly by necessity in terms of the schema. There will be other situations in which an Object annotation is not required. A common example would be parameters appended with “of the Universe” - in such a case, a “Universe” object would most likely be superfluous.

The idea of an Object annotation is that it is a specific object that the measurement relates to (for example, “NCG 0501”, “Gamma Ori”, or similar), rather than a class of objects, such as “galaxies”. The grey area here is that sometimes you will come across a phrase such as, “the critical mass of white dwarf stars”, where it is unclear if that is a single ParameterName, or a “critical mass” ParameterName of a “white dwarf” Object. In such cases please use separate ParameterName and Object annotations (so, annotate “white dwarf” as an Object), but this does not mean that you need to annotate every single example of “white dwarf” as an Object - just the ones where it is used as an Object in the sentence.

ConfidenceLimit

An additional detail included with many measurements is the confidence limit of the stated uncertainties, as in the following example:

H _ { 0 } = 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 } ( 1 \sigma )

T1 ParameterSymbol 0 9 H _ { 0 }

T2 MeasuredValue 12 54 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 }

T3 ConfidenceLimit 55 67 ( 1 \sigma )

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

In such cases, please annotate the confidence limit value and any necessary “unit” (e.g. “\sigma” or “%”), but leave off any additional text (e.g. “confidence limit” or “C.L.”), as in:

The new limit on the tensor-to-scalar ratio is r < 0.22 \mbox { ( 95 \% CL ) }

T1 ParameterName 21 43 tensor-to-scalar ratio

T2 Constraint 47 55 r < 0.22

T3 ConfidenceLimit 66 71 95 \%

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

This annotation may then be linked to a measurement annotation using the Confidence relation, as discussed here.

Definition

It is beneficial to distinguish mathematical symbols appearing inside equations from those appearing as independant entities in a sentence. To this end, we also have a Definition annotation, which should be used to annotate equations of the form SYMBOL = EXPRESSION, as in:

...mass density parameter \Omega _ { M } = 1 - \Omega _ { \Lambda }...

T1 ParameterName 3 25 mass density parameter

T2 ParameterSymbol 26 40 \Omega _ { M }

T3 Definition 43 67 1 - \Omega _ { \Lambda }

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Defined Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

If you encounter a mathematical expression outside of an equation (i.e. there is no equals sign present), determine if the expression qualifies as a physical quantity in its own right - for instance, is there a measurement of this quantity provided in the text? In such cases, annotate the expression as a ParameterSymbol, and associate it normally with any ParameterName, MeasuredValue, or Constraint annotations. An example of this would be:

\Omega _ { b } h ^ { 2 } = 0.034 ^ { +0.007 } _ { -0.007 }

T1 ParameterName 0 24 \Omega _ { b } h ^ { 2 }

T2 MeasuredValue 27 58 0.034 ^ { +0.007 } _ { -0.007 }

(See on arXiv)

Please note that Definitions do not always appear with an equals sign, but may also be given with a \propto, \sim, \approx, \equiv, or similar symbol. In such cases, please annotate as a simple Definition, with associated Defined relation (see below), as in the following:

A measurement of the parameter \mu \propto \Omega ^ { 2 } _ { b } h ^ { 3 } / \Gamma

T1 ParameterSymbol 31 34 \mu

T2 Definition 43 84 \Omega ^ { 2 } _ { b } h ^ { 3 } / \Gamma

R1 Defined Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

Please note that the Definition should not contain the left-hand-side ParameterSymbol, or the equality symbol. The Definition annotation is specifically for the mathematical expression on the right-hand-side of the equality symbol. Written definitions (i.e. definitions given in written English) should not be annotated using Definition - written definitions are beyond the scope of this project (one day, maybe…). However, do consider if some part of the text in question should be a ParameterName.

Details

The Details annotation is used to annotate information which is required to understand the nature of a measurement, but is not included in the measurement name. For example, consider the following:

We achieve a distance measure at redshift z = 0.275 , of r _ { s } ( z _ { d } ) / D _ { V } ( 0.275 ) = 0.1390 \pm 0.0037 ( 2.7 % accuracy )

T1 ParameterName 13 29 distance measure

T2 ParameterSymbol 57 102 r _ { s } ( z _ { d } ) / D _ { V } ( 0.275 )

T3 MeasuredValue 105 122 0.1390 \pm 0.0037

T4 Details 43 51 z = 0.275

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

R3 Condition Arg1:T3 Arg2:T4

(See on arXiv)

Here we could annotate the ParameterName as “distance measure at redshift z = 0.275”, but this is overly complex and difficult to compare with other instances of “distance measure” (which is, in practice, the actual name of the measured property in this case). The information “at redshift z = 0.275” is important for understanding the measurement, however. As such, we annotate the detail “z = 0.275” as a Details entity, and link it to the MeasuredValue entity (see below for discussion on the relation).

Please use the Details annotation sparingly - it is not meant to replace any of the other annotations here. It’s presence is useful for inferring that additional information is required to contextualise the measurement in question. However, please note that not all Details annotations will be numerical in nature. In the following example, we have an instance of textual contingent information:

We find a \rho _ { DM } ( R _ { 0 } ) = 0.385 \pm 0.027 GeV cm ^ { -3 } for the Einasto profile and \rho _ { DM } ( R _ { 0 } ) = 0.389 \pm 0.025 GeV cm ^ { -3 } for the NFW .

T1 ParameterSymbol 10 37 \rho _ { DM } ( R _ { 0 } )

T2 MeasuredValue 40 71 0.385 \pm 0.027 GeV cm ^ { -3 }

T3 Details 80 95 Einasto profile

T4 ParameterSymbol 100 127 \rho _ { DM } ( R _ { 0 } )

T5 MeasuredValue 130 161 0.389 \pm 0.025 GeV cm ^ { -3 }

T6 Details 170 173 NFW

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Condition Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

R3 Measurement Arg1:T4 Arg2:T5

R4 Condition Arg1:T5 Arg2:T6

(See on arXiv)

which is also useful for contextualising the measurement - especially in this case as the Details allows for the two measurements (which are of the same physical property) to be distinguished.

Relations

In addition to identifying spans of text which correspond to certain entities (names, symbols, numbers, etc.), we are also interested in the relationships between these entities - hence we define “Relations” between entities. Practically, these relations are created by clicking-and-dragging from one entity annotation to another. A window will appear in the brat interface allowing you to specify which type of relation you wish to create between the two entities. Note that the interface will only present the possible relations which may exist between the two entities, as each relation has defined start and end types.

In all cases, the ideal annotation format would be of the form: Object → ParameterName → ParameterSymbol → Measurement (MeasuredValue or Constraint) → ConfidenceLimit.

It is important to remember that we are primarily interested in linguistic relations between the words and symbols in scientific text. So please try and make your relations match the implied grammatical relations that exist in the text, where possible - even if you have an identical ParameterSymbol entity closer to the MeasuredValue, we are interested in the one which the text links to the measurement. The relations we’re annotating are just as important as the entities. The general rule of thumb is that if you need an entity because there should be a relation, then there should be another entity annotation there.

The available relations are discussed in the following sections.

Measurement

A Measurement relation starts at a ParameterName or ParameterSymbol, and ends at a MeasuredValue or Constraint. This relation indicates that the MeasuredValue or Constraint is a stated measurement of the physical entity denoted by the ParameterName/ParameterSymbol. Ideally, all MeasuredValue and Constraint annotations should have an associated Measurement relation, but there are edge cases where it is very difficult to identify an appropriate ParameterName or ParameterSymbol. In such cases, please annotate as fully as possible.

Examples of standard Measurement relations would be:

H _ { 0 } = 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 } ( 1 \sigma )

T1 ParameterSymbol 0 9 H _ { 0 }

T2 MeasuredValue 12 54 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 }

T3 ConfidenceLimit 55 67 ( 1 \sigma )

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

In the framework of the \Lambda CDM model our joint analysis yields a value of H _ { 0 } = 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 } ( 1 \sigma ) with the best fit density parameter \Omega _ { M } = 0.27 \pm 0.03 .

T1 ParameterSymbol 79 88 H _ { 0 }

T2 MeasuredValue 91 133 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 }

T3 ConfidenceLimit 134 146 ( 1 \sigma )

T4 ParameterSymbol 183 197 \Omega _ { M }

T5 MeasuredValue 200 213 0.27 \pm 0.03

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

R3 Measurement Arg1:T4 Arg2:T5

(See on arXiv)

It is possible that a given ParameterName or ParameterSymbol may have multiple measurement values associated with it. In which case simple create multiple relations from a single ParameterName/ParameterSymbol.

Uncertainty

A Uncertainty relation starts at a MeasuredValue and ends at a SeparatedUncertainty, and is used to indicate that the stated uncertainty (given at a separate location in the text) relates to the given measurement.

UncertaintyName

An UncertaintyName relation starts at a ParameterName or ParameterSymbol and ends at a SeparatedUncertainty. It is used to indicate that a SeparatedUncertainty relates to a given name in the text (commonly a ParameterSymbol prefixed by “\Delta” or similar).

Name

A Name relation is between a ParameterName and a ParameterSymbol, and is used to indicate that the given ParameterName is the linguistic name of the ParameterSymbol. For instance, the phrase “Hubble constant” is the linguistic name (ParameterName) for the symbol “H_0” (ParameterSymbol).

It is very likely that many mathematical symbols will be given in the text without reference to a linguistic name, especially in contexts where the symbol is commonly agreed upon within the field (for instance, it is not uncommon for “H_0” and “\Omega_\Lambda” to be used in cosmology papers without explanation). However, please do attempt to find an appropriate span in the text, and remember that the name and symbol may appear in different sentences.

You will also encounter situations in which a name and symbol appear together without a nearby measurement. In such cases there will often be a measurement of the physical entity given later in the text (probably using only the symbol). When this occurs, please ensure you create a relation between the name and symbol which appear together (i.e. the name and symbol which have the strongest linguistic connection), but do not create a Name relation between the ParameterName at the start of the document and the ParameterSymbol at the end (provided that the symbol uses exactly the same text). Any “missing” relations may be easily reconstructed automatically, and the resulting markup in the brat interfacei will be much more readable.

However, if the only name/symbol pair in the text is greatly separated, please do annotate this - we require at least one relation between the spans in a given document.

Property

A Property relation is between an Object and a ParameterName or ParameterSymbol (or, occasionally, a MeasuredValue/Constraint, as discussed below), and is used to indicate that the name or symbol is given as a property of the annotated object. For example:

...we infer the spin parameter of SWIFT J1753.5-0127 to be 0.76 ^ { +0.11 } _ { -0.15 } .

T1 ParameterName 16 30 spin parameter

T2 Object 34 52 SWIFT J1753.5-0127

T3 MeasuredValue 59 87 0.76 ^ { +0.11 } _ { -0.15 }

R1 Property Arg1:T2 Arg2:T1

R2 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

Please include these relations wherever possible, as they are prone to linguistic ambiguity - especially in the cases where there are multiple objects referenced in the same text.

You may encounter situations in which a single instance of a ParameterName/ParameterSymbol is used to refer to measurements of multiple objects, as in the following:

... determining the mass and effective temperature of \Iota Ori Aa ( 13.1 \pm 0.1 M _ { \odot } , 32.5 \pm 0.2 kK ) and 10 Lac ( 26.9 \pm 0.3 M _ { \odot } , 36 \pm 1 kK) with ...

T1 ParameterName 20 24 mass

T2 ParameterName 29 50 effective temperature

T3 Object 54 66 \Iota Ori Aa

T4 MeasuredValue 69 95 13.1 \pm 0.1 M _ { \odot }

T5 MeasuredValue 98 113 32.5 \pm 0.2 kK

T6 Object 120 126 10 Lac

T7 MeasuredValue 129 155 26.9 \pm 0.3 M _ { \odot }

T8 MeasuredValue 158 169 36 \pm 1 kK

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T4

R2 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T5

R3 Property Arg1:T3 Arg2:T4

R4 Property Arg1:T3 Arg2:T5

R5 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T7

R6 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T8

R7 Property Arg1:T6 Arg2:T7

R8 Property Arg1:T6 Arg2:T8

(Constructed example.)

In such cases, you may create a property relation from the Object to the specific MeasuredValue/Constraint, along with the Measurement relation from the ParameterName/ParameterSymbol to the MeasuredValue/Constraint.

Confidence

A Confidence relation is between a MeasuredValue or Constraint and a ConfidenceLimit, and is used to relate a measurement with a stated confidence. Note that in many cases a single confidence annotation may be used for several measurements. In which case, simply link the multiple measurements to the single annotation - this is perfectly acceptable in the brat interface.

As an example:

H _ { 0 } = 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 } ( 1 \sigma )

T1 ParameterSymbol 0 9 H _ { 0 }

T2 MeasuredValue 12 54 71 \pm 0.04 { km s } ^ { -1 } Mpc ^ { -1 }

T3 ConfidenceLimit 55 67 ( 1 \sigma )

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

It is also possible that a Confidence relation may be used to express the confidence at which a value is excluded, as in the following example:

\Omega _ { m } = 1 model is excluded at the 97 % confidence level

T1 ParameterValue 0 14 \Omega _ { m }

T2 MeasuredValue 17 18 1

T3 ConfidenceLimit 44 48 97 %

A1 Incorrect T2

R1 Measurement Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Confidence Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

Defined

A Defined relation is between a ParameterName or ParameterSymbol and a Definition, and is used to indicate that the physical entity in question is defined by the mathematical expression in the Definition. Examples of this would be:

...mass density parameter \Omega _ { M } = 1 - \Omega _ { \Lambda }...

T1 ParameterName 3 25 mass density parameter

T2 ParameterSymbol 26 40 \Omega _ { M }

T3 Definition 43 67 1 - \Omega _ { \Lambda }

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Defined Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

the determination of the equation-of-state parameter of dark energy , w = P / ( \rho c ^ { 2 } )

T1 ParameterName 25 67 equation-of-state parameter of dark energy

T2 ParameterSymbol 70 71 w

T3 Definition 74 96 P / ( \rho c ^ { 2 } )

R1 Name Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Defined Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

(See on arXiv)

Condition

A Condition relation is between a MeasuredValue or Constraint and a Details, MeasuredValue, or Constraint, and is used to link contingent information to a measurement annotation. General examples and discussion may be found in the Details section above.

Further to the examples in given in the Details section, there may be situations where a measurement is contingent upon another measurement (for example, a derived value being contingent on best-fit model parameters). In cases such as this, a Condition relation may be used to indicate that one MeasuredValue/Constraint is dependant upon another.

Equivalence

An Equivalence relation is between two ObjectName entities, and indicates that the two entities are equivalent - for example, the two entities may be different names for the same object (such as a full name and an abbreviation), or the author may have used different technical terms to refer to the same underlying object. For example:

We reexamine likelihood analyzes of the Local Group ( LG ) acceleration , paying particular attention to nonlinear effects .

T1 Object 40 51 Local Group

T2 Object 54 56 LG

R1 Equivalence Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

(See on arXiv)

Note that this relation is for instances where two different spans are used to refer to the same object. Do not link identical ObjectName entities with this relation (this may be done automatically). This relation exists for times when different strings of characters are used to refer to the same object.

Contains

A Contains relation is between two ObjectName entities, and indicates that one object is contained within, or is a sub-component of, another. For example, the phrase “dark matter halo” (an ObjectName when it appears in our text) is used to refer to the halo of the “Milky Way” (another ObjectName in our text). We would use a Contains relation to express this. For example:

In the case of the Milky Way, we find a dark matter halo density of ( 4 \pm 0.1 ) \times 10 ^ 7 M _ { \odot } / kpc ^ 3

T1 ObjectName 19 28 Milky Way

T2 ObjectName 40 56 dark matter halo

T3 ParamaterName 57 64 density

T4 MeasuredValue 68 119 ( 4 \pm 0.1 ) \times 10 ^ 7 M _ { \odot } / kpc ^ 3

R1 Contains Arg1:T1 Arg2:T2

R2 Property Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

R3 Measurement Arg1:T3 Arg2:T4

(Constructed example.)

This information is useful for building a heirarchical representation of information, aiding search and cross-linking different measurements.

Note that the direction of this relation is important, and should be made Parent → Child.

Attributes

An attribute is a label associated with an entity annotation. This is used to provide additional information about that annotation - for example, information implied by the context, but not actually included in the span itself.

An attribute may be added to an annotation when the annotation is created, or by double clicking on an existing annotation. At the bottom of the window which appears in these cases will be a list of available attributes for the annotation - simply click on the attribute name to toggle it on/off. Multiple attributes may be placed on the same annotation. Note that attributes are entity-type specific, and so it is possible that no options for attributes may appear for a given entity type.

For this project, only MeasuredValue and Constraint entities have available attributes. These are detailed below.

FromLiterature

The FromLiterature attribute is used to indicate that a given MeasuredValue or Constraint is a quoted value from the scientific literature (either from a specific, named source, or merely an accepted value in the community). Such values are usually clearly declared as such in the text.

Incorrect

The Incorrect attribute is used to indicate that the measurement annotation has been deemed incorrect by the authors of the paper. Usually this will be for a quoted value, where the authors are referencing a value from literature which their work disagrees with (they may have a competing value of their own given in the text). However, it is also possible that the authors provide their own determination of a given quantity, and note its disagreement with the literature value, and conclude that there is some underlying problem in their assumptions or technique - whilst rare, this can occur.

AcceptedValue

The AcceptedValue attribute is used to indicate that a given measurement is presented as the correct one - this is useful in cases where there are multiple determinations of a given quantity presented by the authors. If one measurement is indicated as being the accepted/final value, please add this attribute.

UpperBound and LowerBound

The UpperBound and LowerBound attributes are used to indicate that a number constitutes a constraint, but does not have the equality operators for the constraint nature to be simply inferred. For instance, if we have the Constraint annotation “\Omega_\Lambda < 0.7”, we can automate the process of inferring that this is an upper bound on the property “\Omega_\Lambda”. However, in the following example:

Allowing the inclination to be a free parameter we find a lower limit for the spin of 0.90 , this value increases to that of a maximal rotating black hole when the inclination is set to that of the orbital plane of J1655-40 .

T1 ParameterName 13 24 inclination

T2 ParameterName 78 82 spin

T3 Constraint 86 90 0.90

T4 ParameterName 164 175 inclination

T5 Object 215 223 J1655-40

R1 Measurement Arg1:T2 Arg2:T3

A1 LowerBound T3

(See on arXiv)

the linguistics of the sentence must be taken into account before the nature of the constraint may be inferred - hence we require the annotator to include this information in the annotation. Also of note here is that the ParameterName also requires a separate annotation.

(In the above example, hover over the Constraint annotation to see that it has the LowerBound attribute.)

Notes

- As a reminder, please do not create any overlapping annotations - our later analysis will assume as much, and it simplifies the interpretation of your annotations on our end.

Cases to Ignore

We use an automatic process to select article abstracts for annotation, which uses simple rules to decide whether or not an article reports measurements which we may annotate. This system is not perfect, and will occasionally suggest articles which are unsuited to our annotation schema. Sometimes this is simply that the article does not truly contain a “measurement” (although it will contain text spans which resemble a common pattern for a measurement), or it could be that the article is providing a measurement of somethign overly specific (for example, “58 \pm 2 % of our sample of white dwarf stars have a mass below the sample average”, or something else equally contrived).

In such cases, please do not create any annotations for the abstract (or delete any you have already made) and move on to the next abstract.

Here is a list of cases you should ignore (this list may be added to as annotators provide feedback to us, so do check back if you find something unusual, as it may have found its way to this list already):

- All measurements in abstract relate to specific properties of a non-standard sample (for instance, a sample of stars selected for this specific paper). Please note that papers using specific samples may still produce results which are intended to generalise, and these abstracts should still be annotated.

Some papers which are known to be complicated examples are given here:

Contact

If you encounter issues with your annotation work, or have questions regarding logging in or using brat, please contact us by email here.

If you need to refer to a specific annotation when corresponding, please note that you can find a link to an annotation by double clicking in the annotation in the brat interface and clicking “Link” in the right hand side of the “Text” section in the resulting window.